Homeowners in Carlsbad and Vista often notice issues like uneven temperatures, strange sounds, short cycling, or a thermostat that will not hold a set point. For hvac contractor Carlsbad calls, start by confirming thermostat settings, replacing batteries, checking breakers, and verifying that vents are open and filters are not clogged. For furnace repair in vista, ca, note any error codes, ignition attempts, or unusual odors, and avoid repeated resets if the issue returns quickly. If the air conditioner not cooling Carlsbad, document outdoor unit behavior, airflow at registers, and whether ice is present on lines. Veterans Heating and Air Conditioning, Plumbing and Electrical provides diagnostics, explains repair and replacement options, and can also help with heat pumps, ductless systems, indoor air quality, and routine maintenance. Because many comfort issues tie into other home systems, our team also supports plumbing and electrical service so homeowners can address related needs during the same service window.

If the air conditioner not cooling Carlsbad, document outdoor unit behavior, airflow at registers, and whether ice is present on lines. Veterans Heating and Air Conditioning, Plumbing and Electrical provides diagnostics, explains repair and replacement options, and can also help with heat pumps, ductless systems, indoor air quality, and routine maintenance. Because many comfort issues tie into other home systems, our team also supports plumbing and electrical service so homeowners can address related needs during the same service window..jpg/120px-ARRA_Puts_Retired_Fire_Chief_Back_To_Work_At_WIPP_(7421731412).jpg)

Maghanap

Mga Sikat na Post

-

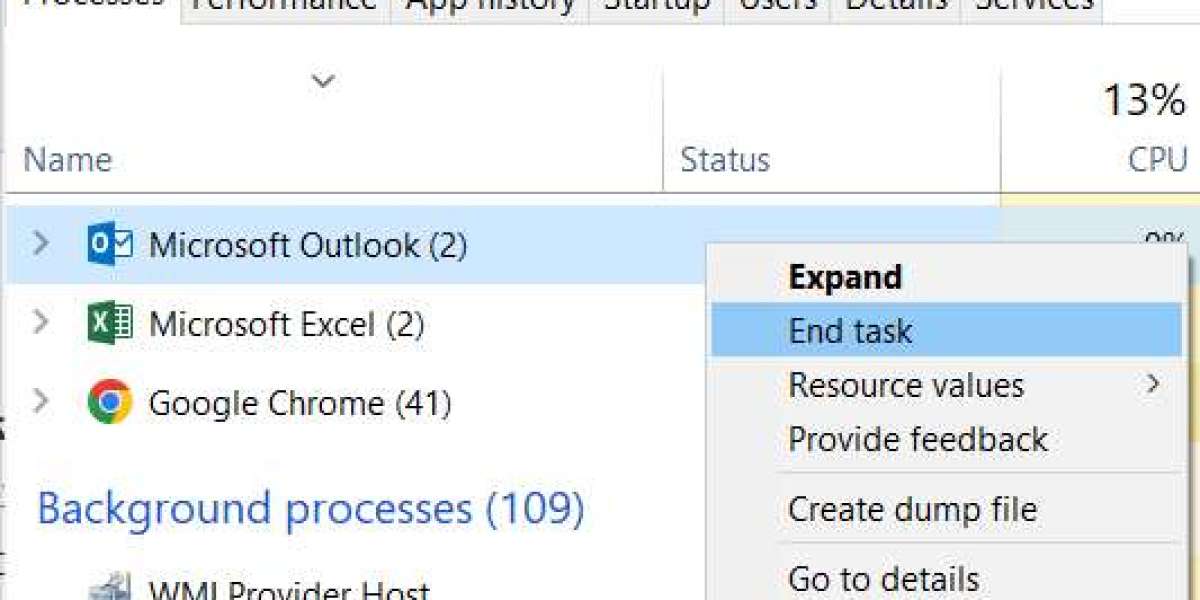

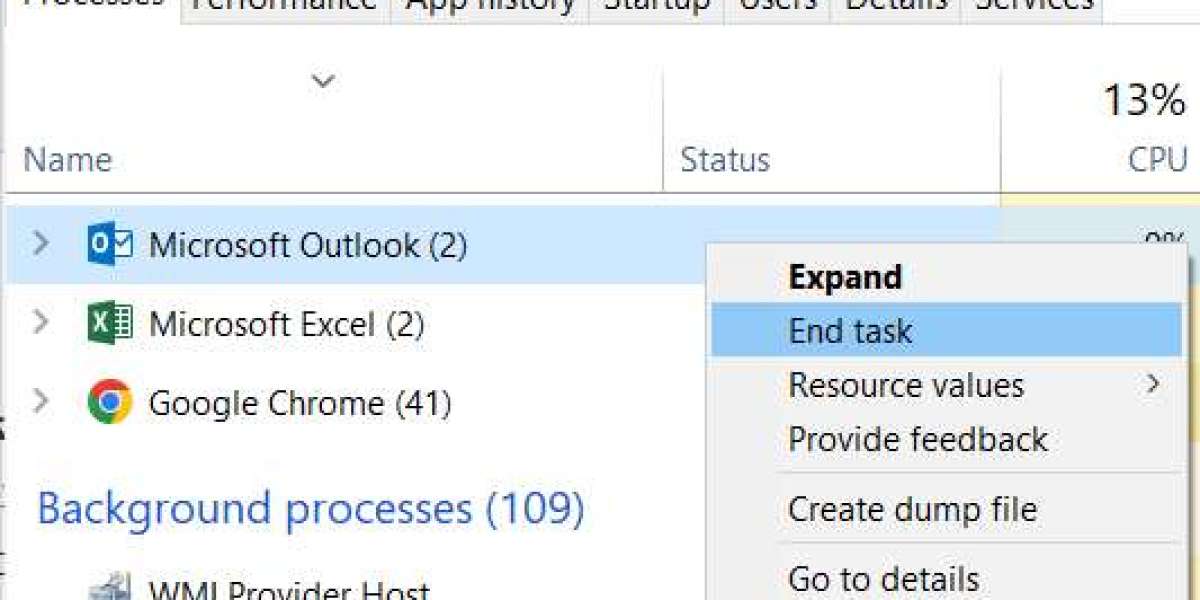

Repair an Office application

Sa pamamagitan ng ashlykime82679

Repair an Office application

Sa pamamagitan ng ashlykime82679 -

Global Power Steering Fluids Market Industry Insights, Trends, Outlook, Opportunity Analysis Forecast To 2025-2034

Sa pamamagitan ng kertina2

Global Power Steering Fluids Market Industry Insights, Trends, Outlook, Opportunity Analysis Forecast To 2025-2034

Sa pamamagitan ng kertina2 -

Poker Room Online Non AAMS: Analisi delle Dinamiche Competitive e Implicazioni per il Giocatore Italiano

Sa pamamagitan ng devidweb

Poker Room Online Non AAMS: Analisi delle Dinamiche Competitive e Implicazioni per il Giocatore Italiano

Sa pamamagitan ng devidweb -

Outlook 2013 2016 stuck on "loading profile" for about 30 seconds Software & Applications

Sa pamamagitan ng harrisleong515

Outlook 2013 2016 stuck on "loading profile" for about 30 seconds Software & Applications

Sa pamamagitan ng harrisleong515 -

Tree Service Springfield Tips for Safer Trees

Sa pamamagitan ng latoshaoliver1

Mga kategorya

- Mga Kotse at Sasakyan

- Komedya

- Ekonomiks at Kalakalan

- Edukasyon

- Aliwan

- Mga Pelikula at Animasyon

- Paglalaro

- Kasaysayan at Katotohanan

- Live na Estilo

- Natural

- Balita at Pulitika

- Tao at Bansa

- Mga Alagang Hayop at Hayop

- Mga Lugar at Rehiyon

- Agham at teknolohiya

- Palakasan

- Paglalakbay at Mga Kaganapan

- Iba pa