Strategic Approach to Low-Stake Gaming Platforms

Digital gambling venues have evolved dramatically in their landscape, with venues now catering to participants across all budget ranges. Entry-level deposit thresholds have become a key factor in platform selection, particularly for new players trying things out or seasoned gamblers managing their bankrolls prudently.

Understanding Entry Barriers in Digital Gaming

Budget-friendly access represents a fundamental element of modern online gambling venues. The base required initial payment typically ranges from $1 to $20, though this changes markedly based on region, payment method, and platform positioning. According to industry data from 2023, approximately 68% of new players start with deposits under $25, demonstrating the market demand for low-barrier entry points.

Payment processing costs directly affect these thresholds. Cryptocurrency transactions often facilitate lower requirements compared to standard financial channels, where processing fees make small deposits economically unviable for operators. The correlation between payment infrastructure and accessibility continues molding how venues structure their financial requirements.

Different Deposit Tiers: Evaluating Value Propositions

Budget-conscious players must explore the connection between deposit amounts and promotional offerings. Platforms frequently structure promotional offers around specific deposit brackets, creating distinct value propositions at multiple entry points.

| Deposit Tier | Usual Bonus Setup | Rollover Terms | Game Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1-$5 | Restricted bonuses | None | Access to all games |

| $10-$20 | 50-100% match bonus | Deposit plus bonus 30-40x | Complete game access |

| $25-$50 | Match bonus 100-150% | 35-45x total amount | Entire catalog with special titles |

| $100+ | Match bonus 150-200% | Deposit plus bonus 40-50x | VIP access + perks |

Considerations for Low-Entry Gaming Platforms

Selecting a venue based exclusively on minimal deposit requirements represents an incomplete strategy. Several crucial factors deserve equal consideration:

- Withdrawal limits: Low deposit requirements mean little if withdrawal minimums exceed what casual players typically earn

- Method limitations: The smallest deposit options often omit certain banking methods, particularly traditional banking options

- Bonus qualification rules: Most promotional offers become available only above specific deposit amounts, practically creating split-tier systems

- Game contribution rates: Slots typically contribute 100% toward playthrough requirements, while traditional games often contribute 10 to 20 percent

- Limited-time deals: Limited-time offers may decrease casino minimum deposit thresholds during promotional periods

- KYC timing requirements: Some operators require identity verification ahead of processing any deposits, irrespective of amount

Risk Management Through Controlled Funding

Low-threshold deposits serve as an efficient bankroll management tool. By controlling initial exposure, players maintain tighter control over gambling outlays while still having access to full game libraries. This technique aligns with responsible gaming principles, allowing individuals to establish personal limits before dedicating substantial funds.

The mental effect of starting small cannot be overstated. Players commencing with small amounts often demonstrate more controlled play patterns, treating the experience as entertainment rather than income generation. This mindset shift often correlates with prolonged platform engagement and better gaming habits.

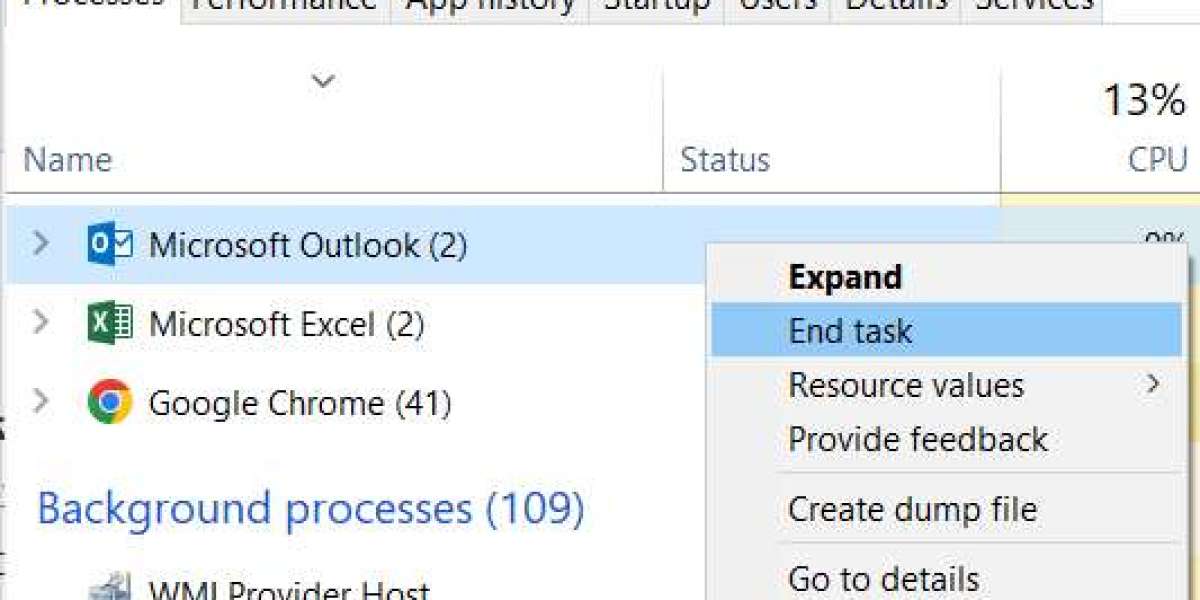

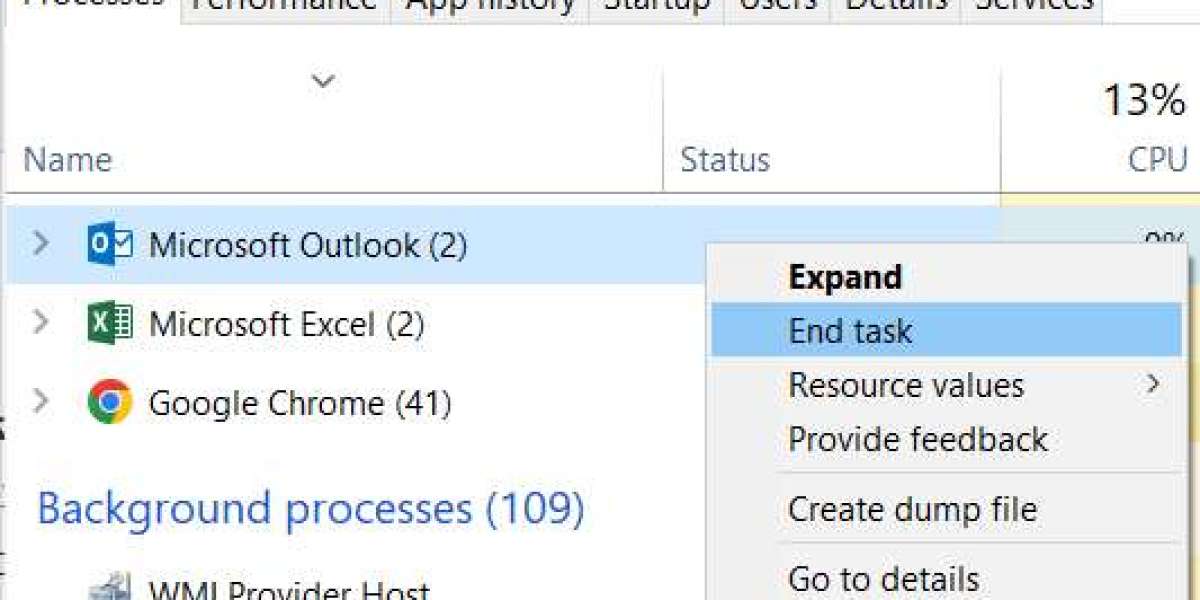

Technology Behind Small Transactions

System payment architecture determines practical minimum thresholds. Conventional merchant processors charge fixed costs and percentages, making transactions under $10 proportionally expensive for operators. Crypto networks and e-wallets offer alternatives with lower transaction costs, permitting genuinely accessible entry points.

Platform selection more and more hinges on payment options. Platforms accepting digital currency, prepaid vouchers, or digital payment systems uniformly offer lower minimums than those banking exclusively on traditional financial methods. The technical infrastructure supporting transactions directly affects accessibility for thrifty participants.

Regulatory Influence on Platforms

Jurisdictional requirements significantly influence deposit structures. Some regulatory agencies mandate maximum deposit limits for new accounts during starting phases, while others require operators to execute affordability checks at specific thresholds. These regulatory requirements create diverse accessibility landscapes across multiple jurisdictions, making geographical considerations relevant to platform selection.

Comprehending how minimum thresholds interact with broader platform features enables knowledgeable decision-making. The optimal approach harmonizes accessibility with value, ensuring entry-level deposits provide valuable gaming experiences rather than only satisfying technical minimums.